The Linux community works, it turns out, because the Linux community isn’t too concerned about work, per se. As much as Linux has come to dominate many areas of corporate computing – from HPC to mobile to cloud – the engineers who write the Linux kernel tend to focus on the code itself, rather than their corporate interests therein.

Such is one prominent conclusion that emerges from Dawn Foster’s doctoral work, examining collaboration on the Linux kernel. Foster, a former community lead at Intel and Puppet Labs, notes, “Many people consider themselves a Linux kernel developer first, an employee second.”

With all the “foundation washing” corporations have inflicted upon various open source projects, hoping to hide corporate prerogatives behind a mask of supposed community, Linux has managed to keep itself pure. The question is how.

Follow the Money

After all, if any open source project should lend itself to corporate greed, it’s Linux. Back in 2008, the Linux ecosystem was estimated to top $25 billion in value. Nearly 10 years later, that number must be multiples bigger, with much of our current cloud, mobile, and big data infrastructure dependent on Linux. Even within a single company like Oracle, Linux delivers billions of dollars in value.

Small wonder, then, that there’s such a landgrab to influence the direction of Linux through code.

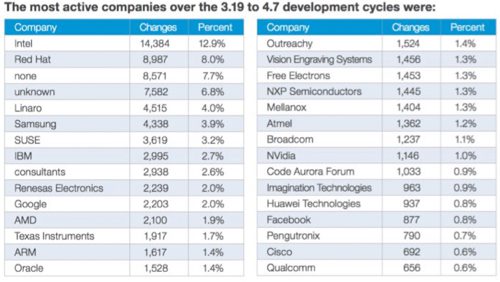

Take a look at the most active contributors to Linux over the last year and it’s enterprise “turtles” all the way down, as captured in the Linux Foundation’s latest report:

Each of these corporations spends significant quantities of cash to pay developers to contribute free software, and each is banking on a return on these investments. Because of the potential for undue corporate influence over Linux, some have cried foul on the supposed shepherd of Linux development, the Linux Foundation. This criticism has become more pronounced of late as erstwhile enemies of open source like Microsoft have bought their way into the Linux Foundation.

But this is a false foe and, frankly, an outdated one.

While it’s true that corporate interests line up to throw cash at the Linux Foundation, it’s just as true that this cash doesn’t buy them influence over code. In the best open source communities, cash helps to fund developers, but those developers in turn focus on code before corporation. As Linux Foundation executive director Jim Zemlin has stressed:

“The technical roles in our projects are separate from corporations. No one’s commits are tagged with their corporate identity: code talks loudest in Linux Foundation projects. Developers in our projects can move from one firm to another and their role in the projects will remain unchanged. Subsequent commercial or government adoption of that code creates value, which in turn can be reinvested in a project. This virtuous cycle benefits all, and is the goal of any of our projects.”

Anyone that has read Linus Torvalds’ mailing list commentaries can’t possibly believe that he’s a dupe of this or that corporation. The same holds true for other prominent contributors. While they are almost universally employed by big corporations, it’s generally the case that the corporations pay developers for work they’re already predisposed to do and, in fact, are doing.

After all, few corporations would have the patience or risk profile necessary to fund a bunch of newbie Linux kernel hackers and wait around for years for some of them to maybe contribute enough quality code to merit a position of influence on the kernel team. So they opt to hire existing, trusted developers. As noted in the 2016 Linux Foundation report, “The number of unpaid developers continue[d] its slow decline, as Linux kernel development proves an increasingly valuable skill sought by employers, ensuring experienced kernel developers do not stay unpaid for long.”

Such trust is bought with code, however, not corporate cash. So none of those Linux kernel developers is going to sell out the trust they’ve earned for a brief stint of cash that will quickly fade when an emerging conflict of interest compromises the quality of their code. It makes no sense.

Not Kumbaya, but not Game of Thrones, Either

Ultimately, Linux kernel development is about identity, something Foster’s research calls out.

Working for Google may be nice, and perhaps carries with it a decent title and free drycleaning. Being the maintainer for a key subsystem of the Linux kernel, however, is even harder to come by and carries with it the promise of assured, highly lucrative employment by any number of companies.

As Foster writes, “Even when they enjoy their current job and like their employer, most [Linux kernel developers] tend to look at the employment relationship as something temporary, whereas their identity as a kernel developer is viewed as more permanent and more important.”

Because of this identity as a Linux kernel developer first, and corporate citizen second, Linux kernel developers can comfortably collaborate even with their employer’s fiercest competitors. This works because the employers ultimately have limited ability to steer their developers’ work, for reasons noted above. Foster delves into this issue:

“Although companies do sometimes influence the areas where their employees contribute, individuals have quite a bit of freedom in how they do the work. Many receive little direction for their day-to-day work, with a high degree of trust from their employers to do useful work. However, occasionally they are asked to do some specific piece of work or to take an interest in a particular area that is important for the company.

Many kernel developers also collaborate with their competitors on a regular basis, where they interact with each other as individuals without focusing on the fact that their employers compete with each other. This was something I saw a lot of when I was working at Intel, because our kernel developers worked with almost all of our major competitors.”

The corporations may compete on chips that run Linux, or distributions of Linux, or other software enabled by a robust operating system, but the developers focus on just one thing: making the best Linux possible. Again, this works because their identity is tied to Linux, not the firewall they sit behind while they code.

Foster has illustrated this interaction for the USB subsystem mailing list (between 2013 and 2015), with darker lines portraying heavier email interaction between companies:

In pricing discussions the obvious interaction between a number of companies might raise suspicions among antitrust authorities, but in Linux land it’s simply business as usual. This results in a better OS for all the parties to go out and bludgeon each other with in free market competition.

Finding the Right Balance

Such “coopetition,” as Novell founder Ray Noorda might have styled it, exists among the best open source communities, but only works where true community emerges. It’s tough, for example, for a project dominated by a single vendor to achieve the right collaborative tension. Kubernetes, launched by Google, suggests it’s possible, but other projects like Docker have struggled to reach the same goal, in large part because they have been unwilling to give up technical leadership over their projects.

Perhaps Kubernetes worked so well because Google didn’t feel the need to dominate and, in fact, wants other companies to take on the mantle of development leadership. With a fantastic code base that solves a major industry need, a project like Kubernetes is well-positioned to succeed so long as Google both helps to foster it and then gets out of the way, which it has, encouraging significant contributions from Red Hat and others.

Kubernetes, however, is the exception, just as Linux was before it. To succeed because of corporate greed, there has to be a lot of it, and balanced between competing interests. If a project is governed by just one company’s self-interest, generally reflected in its technical governance, no amount of open source licensing will be enough to shake it free of that corporate influence.

Linux works, in short, because so many companies want to control it and can’t, due to its industry importance, making it far more profitable for a developer to build her career as a Linux developer rather than a Red Hat (or Intel or Oracle or…) engineer.

This article was originally published in October, 2017